Published:

This guest post is part of the CAP Research Community Series. This series highlights research, applications, and projects created with Caselaw Access Project data.

Jonathan H. Choi is a Fellow at the New York University School of Law and will join the University of Minnesota Law School as an Associate Professor in August 2020. This post summarizes an article recently published in the May 2020 issue of the New York University Law Review, titled An Empirical Study of Statutory Interpretation in Tax Law, available here on SSRN.

Do agencies interpret statutes using the same methodologies as courts? Have agencies and courts changed their interpretive approaches over time? And do different interpretive tools apply in different areas of law?

Tax law provides a good case study for all these questions. It has ample data points for comparative analysis: the IRS is one of the biggest government agencies and has published a bulletin of administrative guidance on a weekly basis for more than a hundred years, while the Tax Court (which hears almost all federal tax cases) has been active since 1942. By comparing trends in interpretive methodology at the IRS and Tax Court, we can see how agency and court activity has evolved over time.

The dominant theoretical view among administrative law scholars is that agencies ought to take a more purposivist approach than courts—that is, agencies are more justified in examining indicia of statutory meaning like legislative history, rather than focusing more narrowly on the text of the statute (as textualists would). Moreover, most administrative law scholars believe that judicial deference (especially Chevron) allows agencies to select their preferred interpretation of the statute on normative grounds, when choosing between multiple competing interpretations of statutes that are “reasonable.”

On top of this, a huge amount of tax literature has discussed “tax exceptionalism,” the view that tax law is different and should be subject to customized methods of interpretation. This has a theoretical component (the tax code’s complexity, extensive legislative history, and specialized drafting process) as well as a cultural component (the tax bar, from which both the IRS and the Tax Court draw, is famously insular).

That’s the theory—but does it match empirical reality? To find out, I created a new database of Internal Revenue Bulletins and combined it with Tax Court decisions from the Caselaw Access Project. I used Python to measure the frequency of terms associated with different interpretive methods in documents produced by the IRS, the Tax Court, and other federal courts. For example, “statutory” terms discuss the interpretation of statutes, “normative” terms discuss normative values like fairness and efficiency, “purposivist” terms discuss legislative history, and “textualist” terms discuss the language canons and dictionaries favored by textualists.

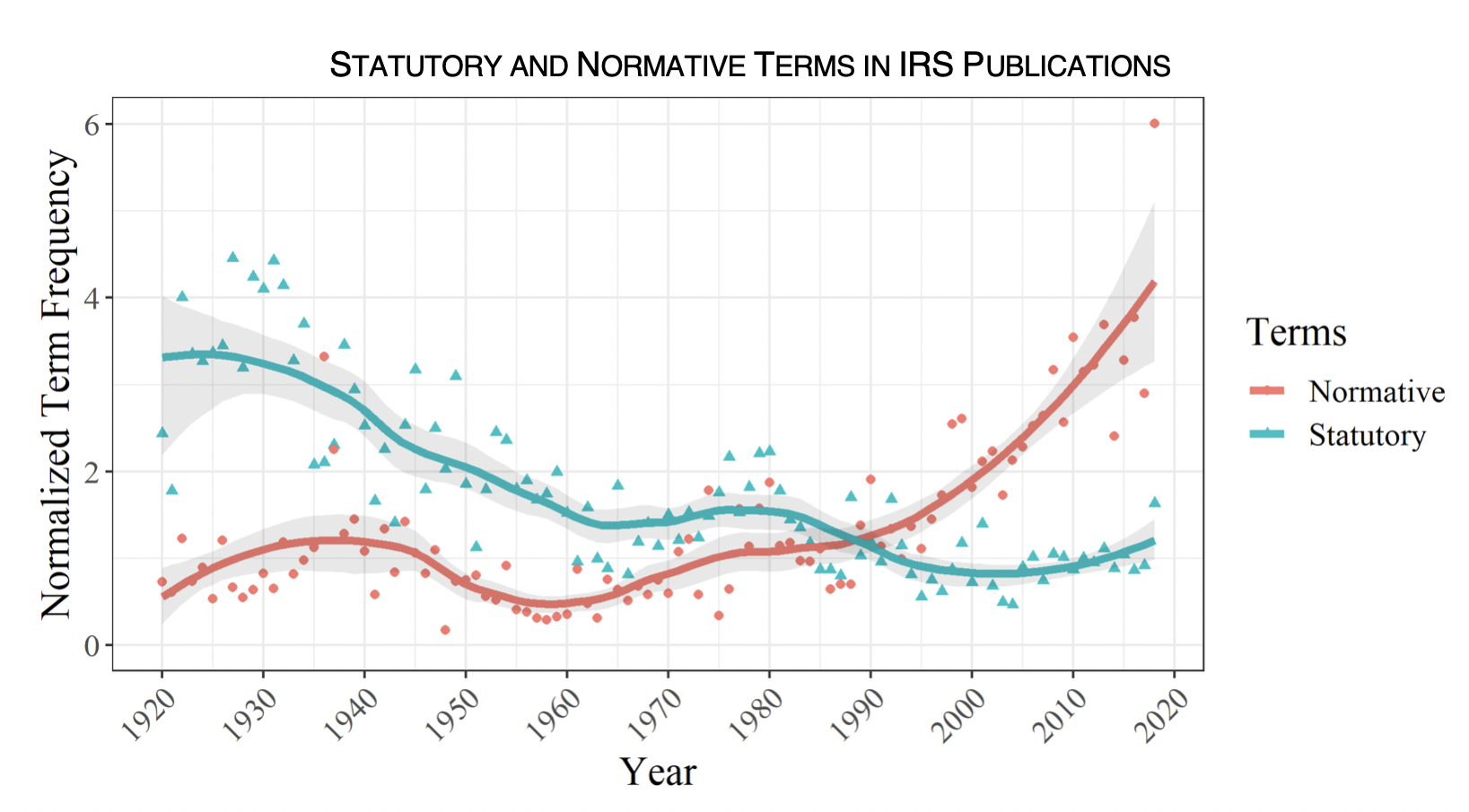

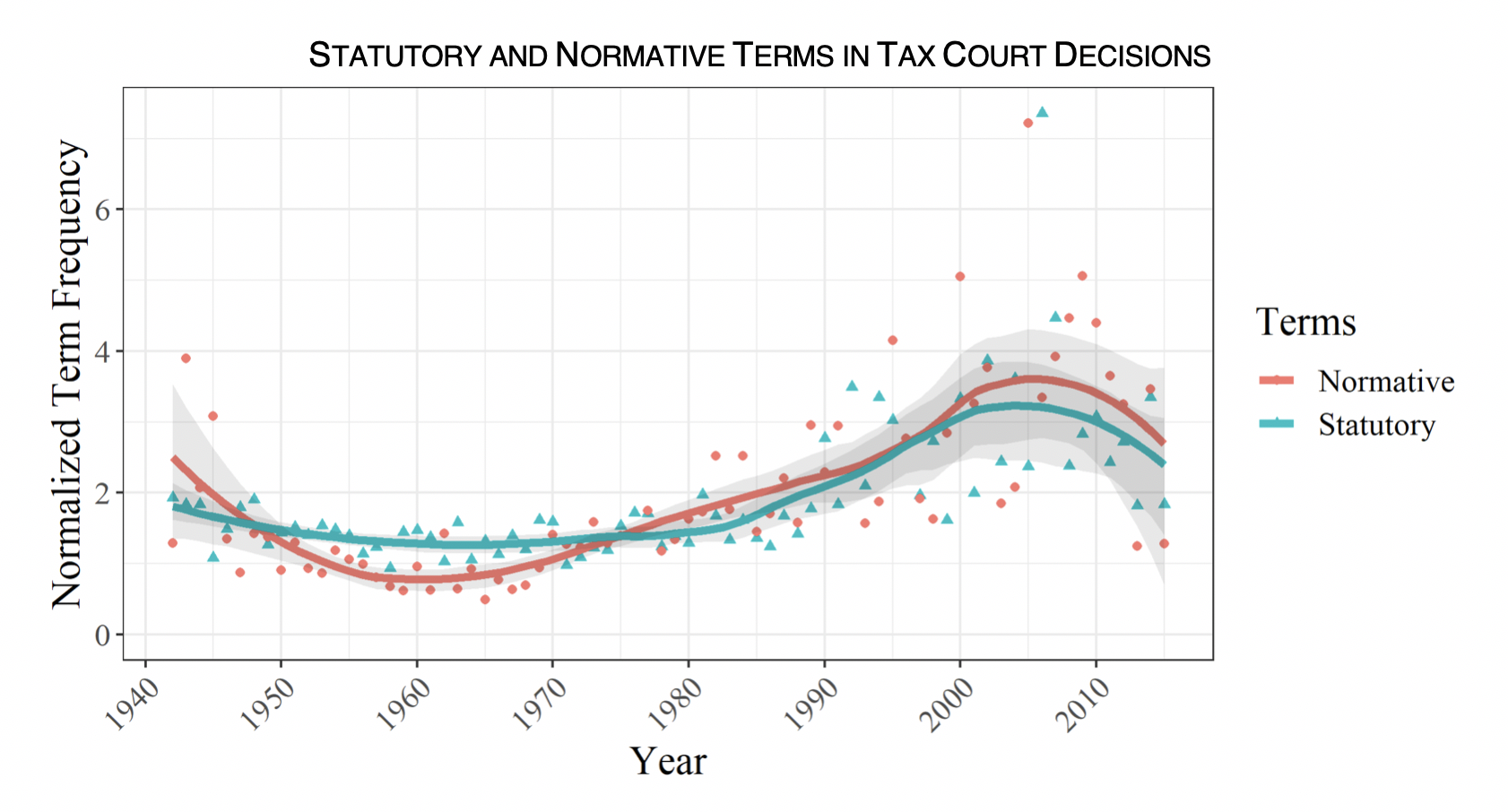

It turns out that the IRS has indeed shifted toward considering normative issues rather than statutory ones:

In contrast, the Tax Court has fluctuated over time but has been stable in the relative mix of normative and statutory terms:

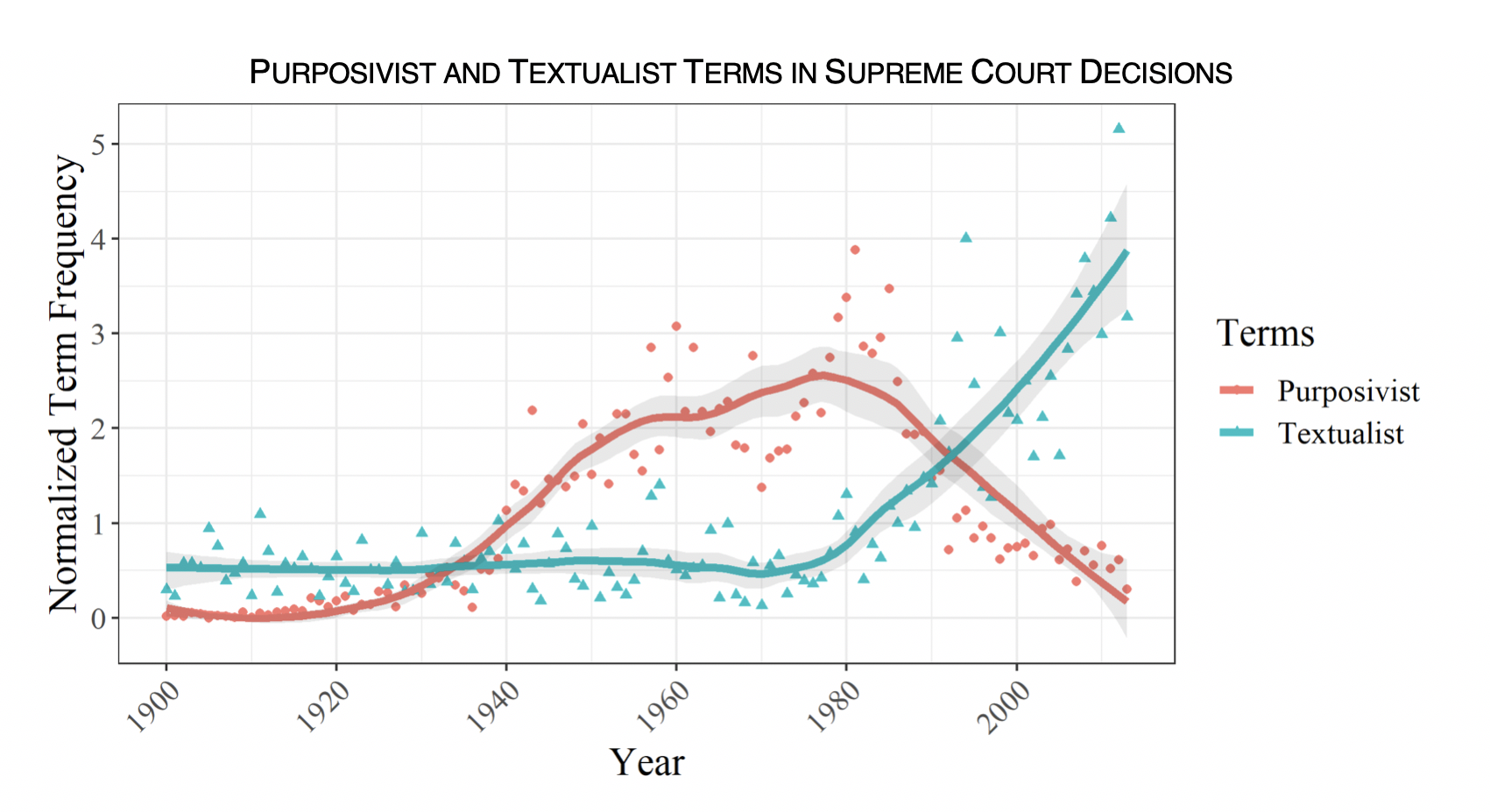

On the choice between purposivism and textualism, we can compare the IRS and the Tax Court with the U.S. Supreme Court. The classic story at the Supreme Court is that purposivism rose up during the 1930s and 1940s, peaked around the 1970s, and then declined from the 1980s onward, as the new textualism of Justice Scalia and his conservative colleagues began to dominate jurisprudence at the Supreme Court:

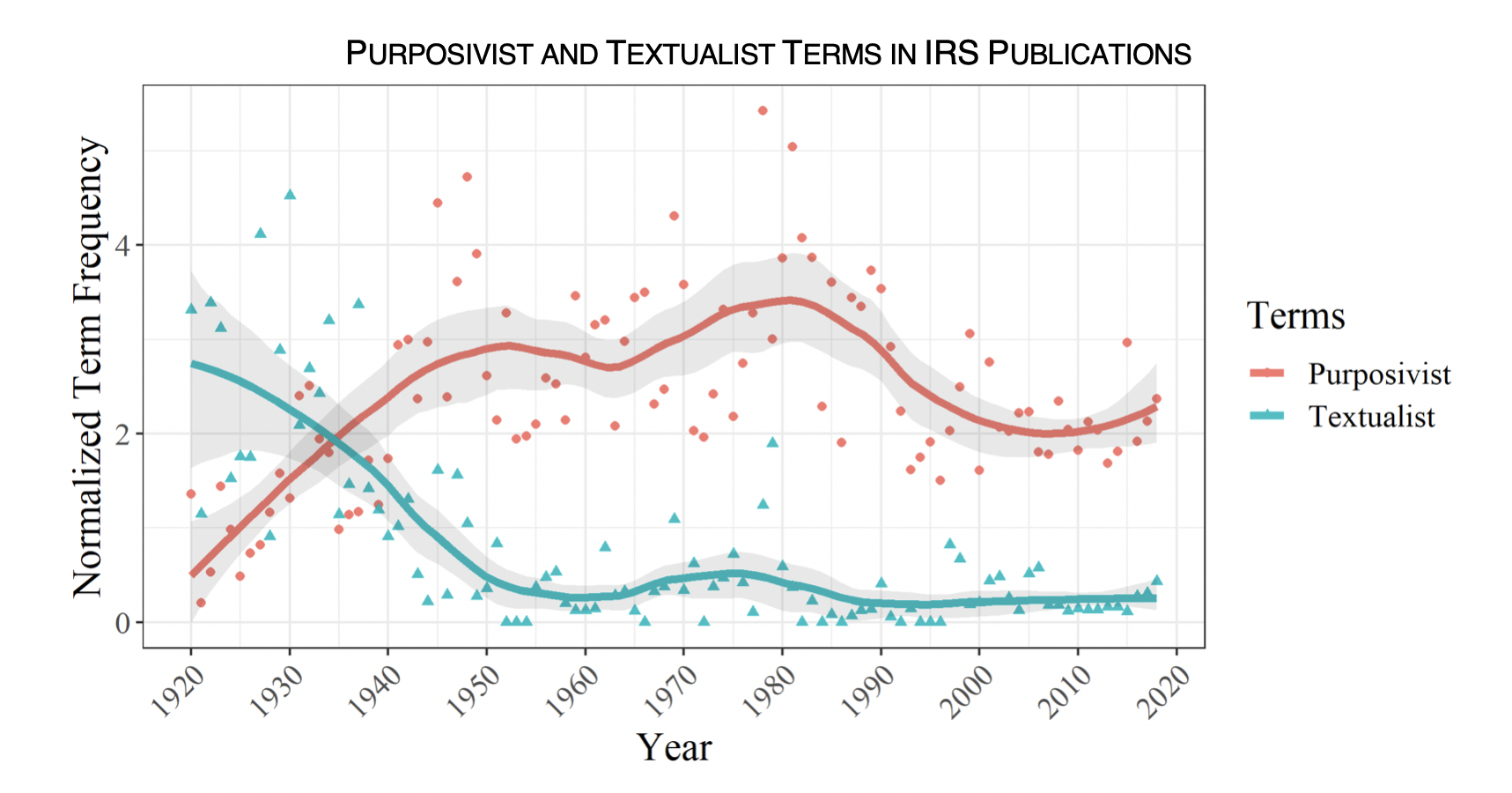

Has the IRS followed the new textualism? Not at all—it shifted toward purposivism in the 1930s and 1940s, but has basically ignored the new textualism:

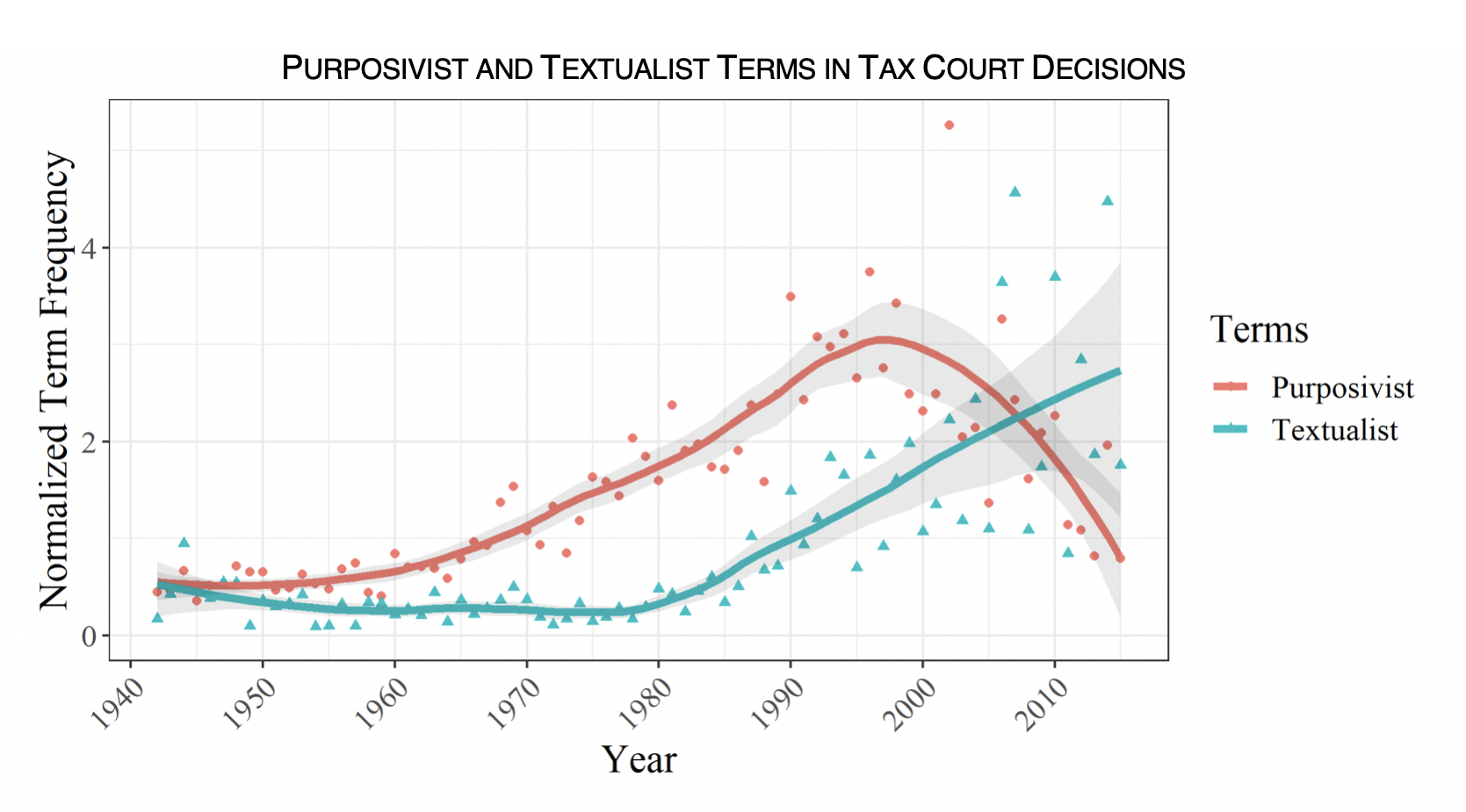

In contrast, the Tax Court has completely embraced the new textualism, albeit with a lag compared to the Supreme Court:

Overall, the IRS has shifted toward making decisions on normative grounds and has remained purposivist, as administrative law scholars have argued. The Tax Court has basically followed the path of other federal courts toward the new textualism, sticking with its fellow courts rather than its fellow tax specialists.

That said, even though the Tax Court has shifted toward textualism like other federal trial courts, it might still differ in the details—it could favor some specific interpretive tools (e.g., certain kinds of legislative history, certain language canons) over others. To test this, I used Python’s scikit-learn package to train an algorithm to distinguish between opinions written by the Tax Court, the Court of Federal Claims (a federal court specializing in money claims against the federal government), and federal District Courts. The algorithm used a simple log-regression classifier, with tf-idf transformation, in a bag-of-words model that vectorized each opinion using a restricted dictionary of terms related to statutory interpretation.

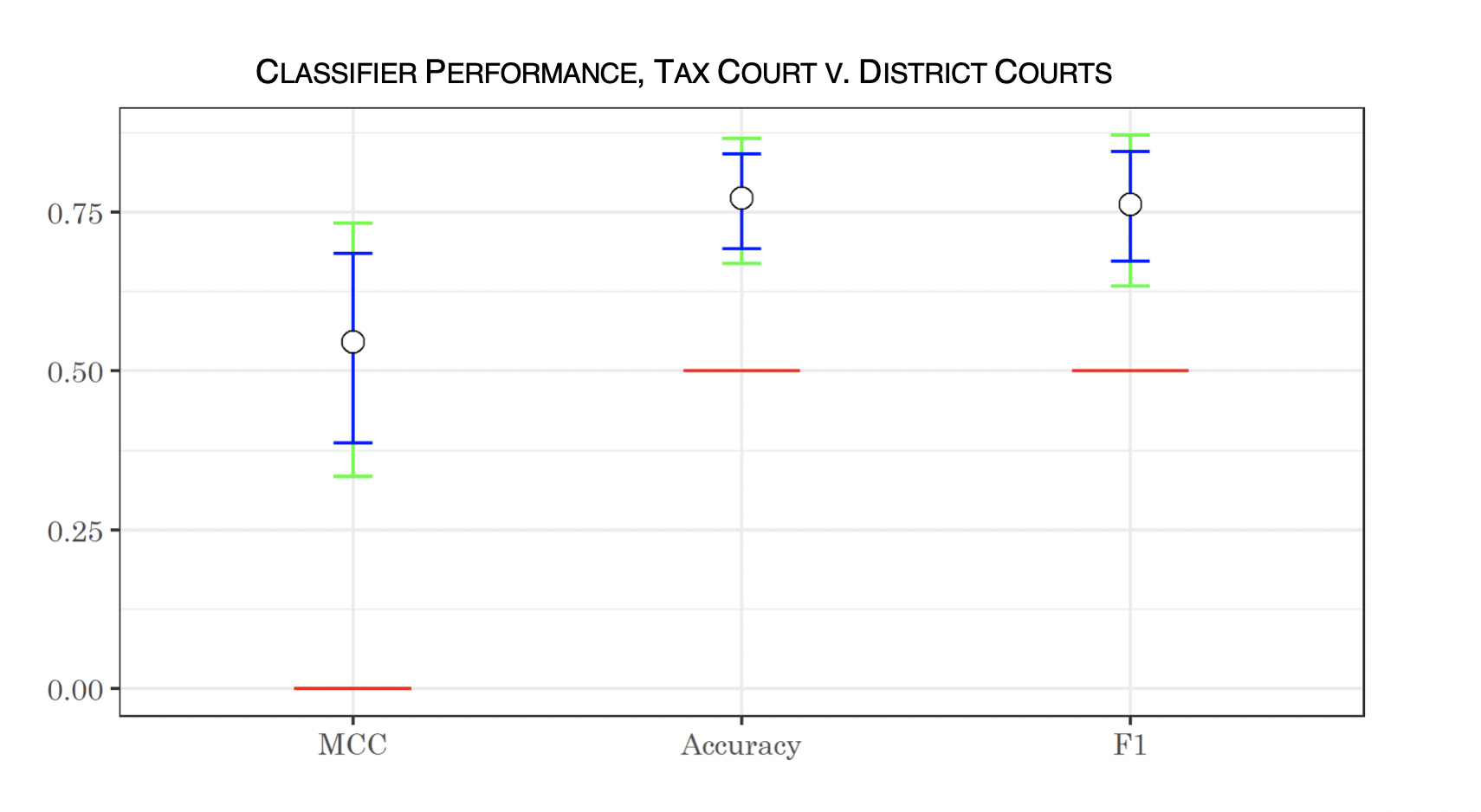

The algorithm performed reasonably well—for example, here are bootstrapped confidence intervals reflecting the performance of the algorithm in classifying opinions between the Tax Court and the district courts, showing Matthews correlation coefficient, accuracy, and F1 score. The white dots represent median performance over the bootstrapped sample; the blue bars show the 95-percent confidence interval, the green bars show the 99-percent confidence interval, and the red line shows the null hypothesis (performance no better than random). The algorithm performed statistically significantly better than random, even at a 99-percent confidence level.

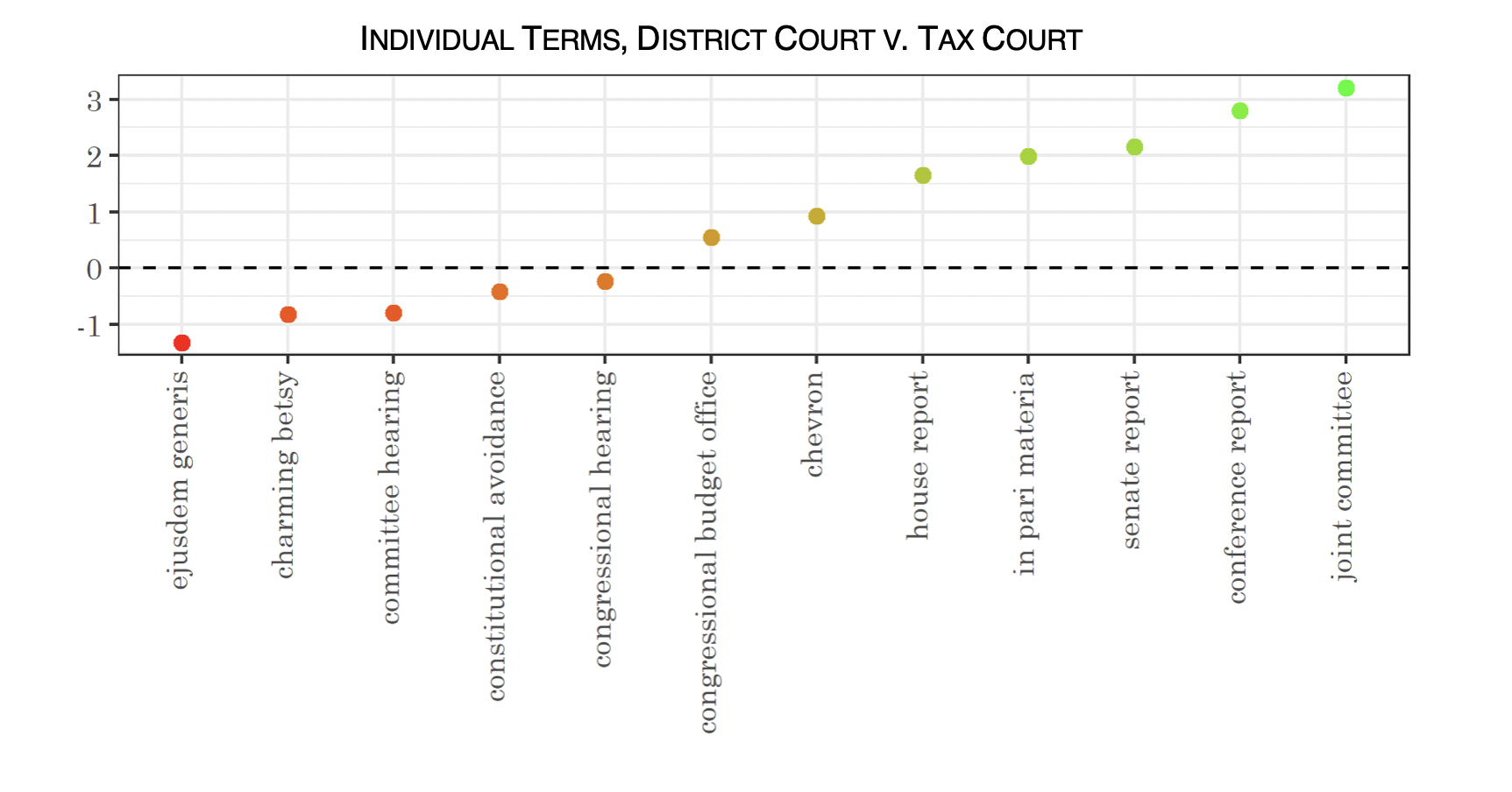

Because the classifier used log regression, we can also analyze individual coefficients to see which particular terms more strongly indicated a Tax Court decision or a District Court decision. The graph of these terms is below, with terms more strongly associated with the District Courts below the line in red, and the terms more strongly associated with the Tax Court above the line in green. These terms were all statistically significant using bootstrapped significance tests and correcting for multiple comparisons (using Šidák correction).

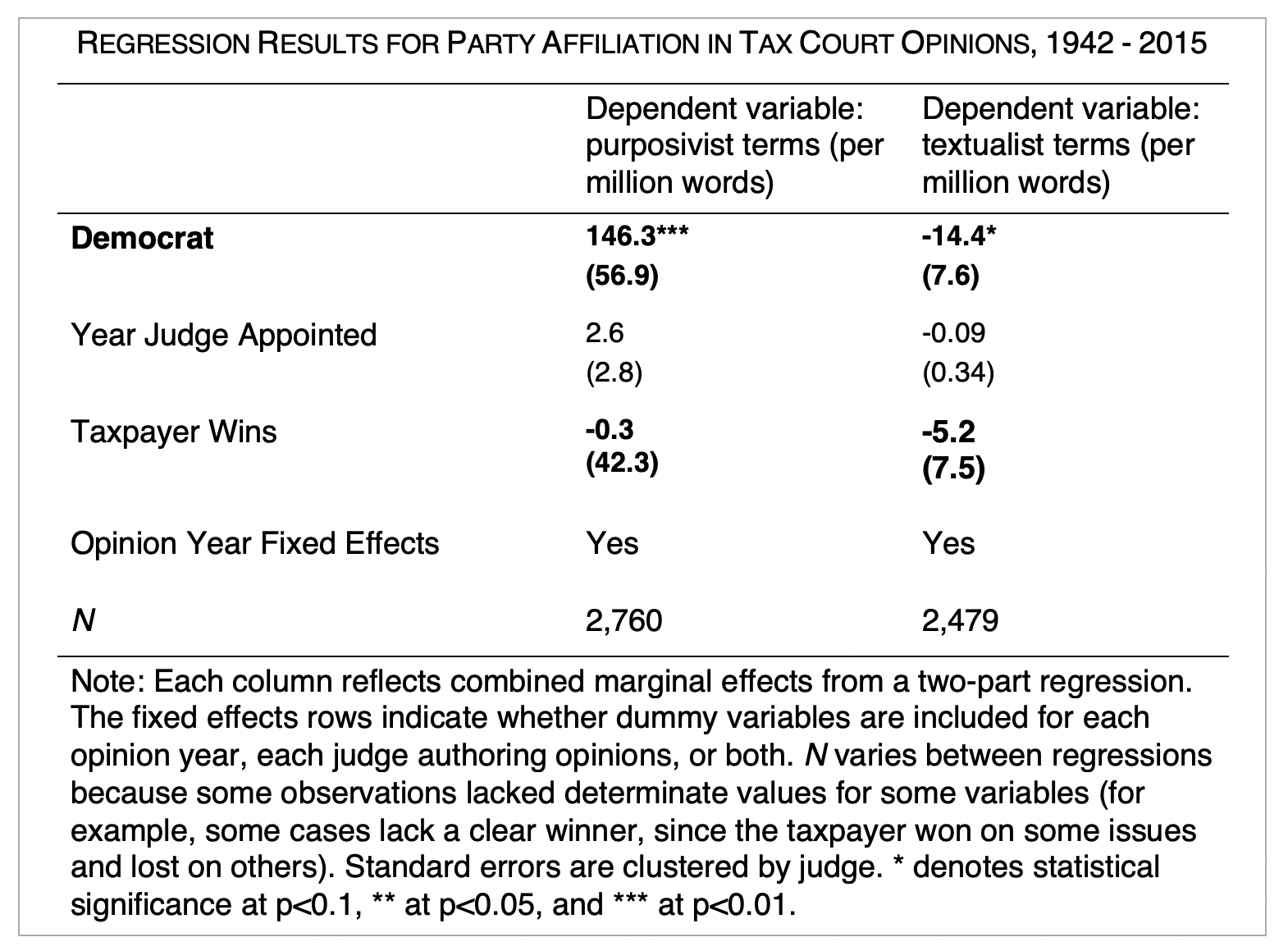

Finally, I used regression analysis (two-part regression to account for distributional issues in the data) to test whether the political party of the Tax Court judge and/or the case outcome could predict whether an opinion was written in more textualist or purposivist language. The party of the Tax Court judge was strongly predictive of methodology; but case outcome (whether the taxpayer won or the IRS won) was not.

The published paper contains much more detail about data, methods, and findings. I’m currently writing another paper using similar methodology to test the causal effect of Chevron deference on agency decisionmaking, so any comments on the methods in this paper are always appreciated!